|

WOMEN

IN THE MARINE MYTHOLOGY OF ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN

WOMEN

IN THE MARINE MYTHOLOGY OF ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN

THEIR ROLES & SYMBOLISMS

George

Pararas-Carayannis & Amanda Laoupi

Presentation

at Pacem in Maribus XXXII, Malta, 5-8 November 2007

Introduction

Throughout human

history and in all ancient societies women constituted a significant

and active force in sustaining the development of communities,

safeguarding resources, educating youth and ensuring continuity

of social, cultural and historical heritage values. Although

this role is not explicitly stated in ancient texts, the impact

and influence of women is evident by implied symbolisms in mythology.

For example the circum-Mediterranean area, a cradle of civilization,

embodied a rich variety of feminine symbolic expressions that

echoes the socio-economic structures of past societies, as well

as the impact of the sea upon their fate. Noteworthy is also

the fact that water was initially part of feminine symbolism.

The Ancient Mediterranean

Sea The Ancient Mediterranean

Sea

The connection between

the feminine element and water involving Mediterranean coastal

communities dates back to Prehistoric Times, as aquatic features,

marine disasters and natural phenomena (tsunami, flooding, stormy

winds & rainfalls, submergence of islands and coastal areas,

coastal erosion and transgression /regression of the seashore,

sea currents, isthmuses and straits, tides and whirlpools) were

strongly interrelated with human life and the progress of civilization

(i.e. navigation, archaeoastronomy, socio-economic contacts via

a sea communication network, wars and geopolitical conflicts).

Women helped increase the awareness of youth through communication

and education and contributed to the remediation of damage caused

by environmental or man-induced hazards. Youths, upon reaching

maturity, were better prepared to assume roles of leadership

in alleviating the impact of environmental hazards threatening

communities and their resources.

The aim of this paper is to: a) illustrate the presence and importance

of the afore-mentioned feminine elements in the marine mythology

of ancient Mediterranean through philological and archaeological

evidence, along with other social and religious testimonies;

b) determine their spatio-temporal distribution within the process

of symbols' migration, and c) group them into coherent cycles

(thematic, phyletic, and other) in order to elucidate their diffusion

and importance in the ancient world.

In brief, the analysis of the mythological symbolisms illustrates

the important and continuous role that women have always played

in protecting marine resources and in helping conserve the heritage

of mankind - a role that must be properly acknowledged, appreciated

and encouraged, now and in the future.

Grouping

the Mediterranean Symbolisms

People of the circum-Mediterranean

area of the ancient world embraced a rich variety of feminine

symbolisms. Survival of their coastal communities, productivity

of their aquatic ecosystems and omens of the priesthood were

all dependent on female deities. Even the splendor and glory

of the accomplishments of these seafaring nations were dependent

upon divine feminine interventions (i.e. the goddess Athena helping

Odysseus). And conversely, so were their hardships and losses

(i.e. Poseidon's

wrath - Scylla & Charybdis). Water was considered a feminine realm by these

ancient communities and was represented by a variety of rich

and diverse feminine, marine symbolisms.

Indicative examples

are the following six categories:

1. The primordial

forces of waters (the Sumerian Nammu - sea goddess and creator

of

heaven, earth, the Egyptian watery chaos out of which Nun emerged

and Isis as

protector of seamen, the Phoenician Astarte called Asherar-yam

'our lady of the sea',

the Greek Tethysand Eurynome);

2. Sea creatures and

monsters (Scylla & Charybdis, Keto, Sirens, Circe & Kalypso);

3. Nymphs and other

aquatic deities (the Minoan Diktynna & Britomartys, Thetis

and

Amphitrite, other Nereids & Oceaneids, Aphrodite);

4. Heroines with a

'suffering' connection to the sea (Andromeda, Danae, Alcyone,

Ino-Leucothea and her child Melikertes -Palaimon);

5. Other sea figures

whose names were associated with the seas (Myrto, Gorge and

Hyrie); and

6. Some special cases

with multi-layered symbolism such as Ariadne and her watery

symbol - the labyrinth, Leto / Asteria & Helle - who fell

onto the sea which took her name - Hellespont. (Pindar frg. 29, 179; Aeschylos, Perses 68)

Limnades

or Limnatides - The nymphs and protectors of fresh water lakes,

marshes, and swamps. The nymphs known as Naiades (Naiads) were

the protectors of springs, fountains, and rivers.

Limnades

or Limnatides - The nymphs and protectors of fresh water lakes,

marshes, and swamps. The nymphs known as Naiades (Naiads) were

the protectors of springs, fountains, and rivers.

The Archetypal

Symbolism of Creation: Waters: A Women's Realm

The world was once

thought to be composed of the four basic elements of water, fire,

earth and air. This concept is of little use to modern science,

which has defined many more elements than these original basic

four. However, the four elements still maintain a powerful symbolism

within the overall realm of imaginative experience, possessing

a strong correspondence to internal states and emotions.

In human spirituality, the element of water was always connected

to the female nature. The cold, moist properties of water symbolize

the enclosing, generating forces of the womb, intuition and the

unconscious mind. In addition, by way of the color blue -the

color of light, electricity and the oceans - consciousness awareness

spirals and cultivates the feminine intuitive, creative part

of the brain.

Historical symbolic representations of water - such as the alchemical/magical

symbol of an inverted triangle that symbolizes the downward,

gravitational flow of water - and the Cup or Chalice - symbolic

of the water triangle - parallel the ancient feminine symbolisms

of a downward pointing triangle (the representation of female

genitalia) and the feminine elements of intuition, gestation,

psychic ability, and the subconscious, respectively. Moreover,

the Cup also stands as a symbol of the Goddess, the womb and

the female generative organs.

One of the earliest symbols in human history is the zigzag, which

was used by Neanderthals around 40,000 B.C., which, represents

water (according

to Marija Gimbutas 1974, 1989 & 1991). The 'M' symbol is interpreted as shorthand

for the zigzag, and it is found on water containers. The chevron

(repetitive form of the 'V') is often found along with the meander,

which is also a water symbol. On the other hand, the meander

was a symbol of the Great Mother Goddess and her life-giving

and nourishing aspects. It was from the divine waters of the

Mother's womb that life came into existence. Some of the earliest

depictions of the Goddess showed her as a hybrid woman/waterbird.

Without water, life cannot be sustained, and for ancient people

waterfowl were an important source of food. Consequently, as

water is an archetype from where all life flows, Gimbutas claims

it to be representative of the Mother Goddess as the Life-Giver.

And, although evidence for the Goddess culture is still disputable,

the new feminist views in archaeology have made many archaeologists

re-evaluate their concepts of civilization.

Later on, in Ancient Egypt, the hieroglyphic sign for water was

a horizontal zigzag line. The small sharp crests on this sign

appear to represent wavelets or ripples on the water's surface.

Egyptian artists indicated bodies of water, such as a lake, or

a pool or the primeval ocean, by placing the zigzag line in a

vertical position and then multiplying it in an equally spaced

pattern. Of significance is the ancient Egyptian name for water,

"uat", which also meant the color green and, for ancient

Egyptians, characterized the hard green stone, the emerald, and

the green feldspar. Of these stones, the emerald is associated

with romantic love and the sensual side of nature; and sacred

to the goddess Aphrodite/Venus, a sea-divinity who was born from

the sea. Some early Greek thinkers conceived the sea-divinities

as feminine primordial powers, since the Goddess of the Sea took

a part in the creation of the world, due to an old belief, in

which life began in the water.

The oceans and other large bodies of water in the world are a

type of middle ground between the activity of rivers and the

passiveness and reflection of lakes. In the ancient world, the

protectors of these water systems, the Sea-deities, the Limnades

(of the lakes, marshes and swamps), and the Naiades (of the springs,

fountains and rivers), maintained the balance. The symbol of

agitated 'troubled waters' has traditionally related to the illusions

and vanities of life. Agitated waters are more subject to climatic

conditions involving wind, while deep waters such as seas, lakes

and wells have a symbolism related to the dead and the supernatural.

Conversely, water plays a major part in various weather phenomena.

Rainstorms and snowstorms involve the free-fall of water from

above to below. Floods occur when containment of water fails.

Tsunamis, hurricanes and tornados involve the movement of water

and turbulence in the seas. Clouds, fog, humidity and mist symbolize

in-between states where water is mixed with air. Like a time

of twilight between night and day, fog and mist are the 'twilight'

states of water and air.

The Dual Nature of

Sea Creatures and Goddesses The Dual Nature of

Sea Creatures and Goddesses

Since ancient times,

washing with water has signified, in both a literal and metaphoric

sense, the process of cleansing, purification, transformation

and metamorphosis. Although water itself may contain the power

to bring about change, it also serves as the medium through which

a god, goddess, or priest exercises change. Change in the form

of physical transformation or metamorphosis is characteristic

of the female nature through menstruation and birth. Water, identified

as female and associated with women, symbolizes seduction and

transformation, a powerful and often feared aspect of women by

men. Death and destruction were usually the fate of mortal men

that were seduced by divine females, as depicted by the paradigms

of Aphrodite, Artemis, Circe and Calypso.

Sea-Goddess Thetis

- wife of Peleus and mother of Achilles, one of the fifty Sea

Nymphs known as Nereïds - riding Hippokampos, a Sea Horse

with a fish tail, and surrounded by dolphins and other Nereids.

Moreover, many cultures

believed that life sprang from the primordial waters that symbolize

life and eternal youth. On the other hand, too much water could

be harmful and life threatening. Water in large quantities, such

as in the sea, contains a power, which can sustain life but can

also destroy life and good order. Numerous traditions around

the world have stories of sea monsters symbolizing the violent

threat of the sea.

In Babylonian mythology, the sea monster Tiamat threatened to

overthrow the gods. However, in both Babylonian and Sumerian

mythology, Tiamat is the salt-water sea, personified also as

a creator-goddess and a primordial mother, as wells as a monstrous

embodiment of primordial chaos. In the Enuma Elish (the Babylonian

epic of creation), she gives birth to the first generation of

gods. She emerged from the waters of the Persian Gulf in the

form of a 'fish-woman', and taught humanity the arts of life,

for example to build cities and to decree laws (Dalley, 1987: 329; Jacobsen, 1968: 104-10; Kramer,

1944). Some scholars

find a linguistic analogy of the word 'Tiamat' to the Greek 'thalassa'

meaning the sea or the 'Tethys' (Burkert, 1993: 92ff.; Jacobsen 1968:105).

In other stories, human sacrifice was necessary to appease these

sea monsters. The sacrificial victim was often a young virgin

who, as in the cases of Andromeda, may be lucky enough to be

rescued at the last moment by a male hero.

Some sea monsters,

which remained located in a single place, were represented as

female. The most notorious of those were Scylla and Charybdis,

symbols of marine disasters and doom in Greek mythology. The

myth of Scylla and Charybdis, is first known by Homer in his

epic poem Odyssey (xii,

55 - 126 /201 - 259, 426/446. See also Apollodorus, 5. 7.20 ff.). Odysseus had been warned by

both Tiresias and Circe of the two monsters Scylla and Charybdis.

In Greek mythology, Scylla was a sea monster that lived underneath

a dangerous rock at one side of the Strait of Messina, opposite

the whirlpool Charybdis. Terrible and horrible freak of the sea,

she devoured the unfortunate seamen, when the heavy sea threw

their ship into her cave. The other terror, Charybdis, was a

gulf nearly on a level with the water. Thrice each day the water

rushed into a frightful chasm, and thrice was disgorged. Any

vessel coming near the whirlpool when the tide was rushing in

must inevitably be engulfed; not Neptune himself could save it.

The roar of the waters as Charybdis engulfed them gave warning

at a distance, but Scylla could nowhere be discerned.

Medusa - A monstrous

chthonic female character - a symbol of disaster - that could

turn those who gazed upon her into stone. She was beheaded by

the hero Perseus

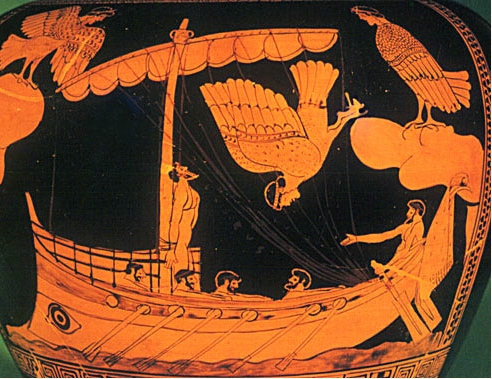

Equally, the mysterious depths

of the ocean and the potentially destructive aspects of the sea

were also personified as female in form, such as Mermaids and

Sirens, the latter memorably encountered by Odysseus. The Sirens

were daughters of the river Acheloos and the Muse Melpomene or

Terpsichore (Apollonius

of Rhodes, 4.805 & 904; Apollodorus, 1.3.4) or Gaia herself (Euripides Hecuba, 169). Hyginus (Fabulae,

110.51) refers to

the tradition that being followers of Persephone, they were punished

by Demeter to turn into marine birds with beautiful girl faces

and charming voices, which lived on an island in the SW shores

of Italy or Sicily. Poor mariners, who were seduced by their

songs, were devoured by them. Homer mentions two of them (Odyssey, xii.56). Odysseus and the Argonauts

were among those who were not seduced by the song of the Sirens

(Orpheus, Argonautics

1281). According

to the oracle, when this happened, the birds dropped into the

sea and drowned (Odyssey,

xii.39-46 & 173). Equally, the mysterious depths

of the ocean and the potentially destructive aspects of the sea

were also personified as female in form, such as Mermaids and

Sirens, the latter memorably encountered by Odysseus. The Sirens

were daughters of the river Acheloos and the Muse Melpomene or

Terpsichore (Apollonius

of Rhodes, 4.805 & 904; Apollodorus, 1.3.4) or Gaia herself (Euripides Hecuba, 169). Hyginus (Fabulae,

110.51) refers to

the tradition that being followers of Persephone, they were punished

by Demeter to turn into marine birds with beautiful girl faces

and charming voices, which lived on an island in the SW shores

of Italy or Sicily. Poor mariners, who were seduced by their

songs, were devoured by them. Homer mentions two of them (Odyssey, xii.56). Odysseus and the Argonauts

were among those who were not seduced by the song of the Sirens

(Orpheus, Argonautics

1281). According

to the oracle, when this happened, the birds dropped into the

sea and drowned (Odyssey,

xii.39-46 & 173).

Odysseus tied to the

mast of his ship and the Sirens

On the contrary, compassion, salvage and initiation were also

attributed to the female nature. Female goddesses, like Isis

and Athena, were protectors of mortals undertaking long open-sea

journeys (such as the Argonautics and the voyage of Odysseus);

and Aphrodite and Ino-Leucothea were the super-natural protectors

of fishermen, sailors, navigation and the entire sea world. When

the Argonauts encountered Charybdis and Scylla and the Wandering

Rocks, it was the Nereids that helped them to steer the ship

through them (Homer,

Iliad XVIII. 36, &III. 140; Apollodorus, 1. 9. 25; Apollononius

Rhodius, 4. 859, 930).

Gendered

Landscapes of the Past and Their Implications for the Present

The basic masculine and feminine

symbolism of the elements finds a correspondence in place symbolism

and the gendered landscapes. The most distinctive characteristics

of world ecosystems relate to climatic conditions and physical

landscape. Climate directly relates to the amount of water contained

in ecosystems and the major aspect of physical landscapes is

verticality. In this sense, the major natural areas of the world

can be divided between those that are dry, wet, low or high.

The quality of dryness and height is related to the elements

of air and fire and that of wetness and lowness to water and

earth. Thus, using these criteria we interpret the division of

the natural world into masculine and feminine places. The basic masculine and feminine

symbolism of the elements finds a correspondence in place symbolism

and the gendered landscapes. The most distinctive characteristics

of world ecosystems relate to climatic conditions and physical

landscape. Climate directly relates to the amount of water contained

in ecosystems and the major aspect of physical landscapes is

verticality. In this sense, the major natural areas of the world

can be divided between those that are dry, wet, low or high.

The quality of dryness and height is related to the elements

of air and fire and that of wetness and lowness to water and

earth. Thus, using these criteria we interpret the division of

the natural world into masculine and feminine places.

Odysseus and the

Oceanid or Atlantid Nymph Calypso was dwelled in a cave on a

lonely island, Ogygia, (Gozo, in the Maltese Archipelago)

Although the sea world

has always been a feminine realm since early prehistory, gender

dichotomies have existed. Anthropological linguistics of the

Mediterranean illustrates the 'taboos' of the aquatic psychology

and marine folklore, expressed through sexual dimorphism. For

example, the ship (a male symbol), which has a feminine name

in English (ship) and Latin (navis), 'penetrates' into the female

sea. But nevertheless, women were usually not allowed to go on

board. Gender dichotomies such as these have served to reinforce

gender differences between activities over time, and further

define feminine and masculine roles in society. The majority

of ethnographic evidence has suggested that, during ancient times,

gender differences between activities in feminine realms existed,

such as open-sea fishing, a mainly male task, and shellfish gathering,

a mainly female task.

The degree to which there are innate differences between male

and female behaviors is one of the most challenging issues in

the study of gender behavior today. Understanding gender preferences

for particular types of tasks assists both men and women, and

ultimately youths, to expand their awareness through communication

and education into new fields of work and/or learn how to utilize,

to a better degree, the resources around them.

Women's productive roles in the value of water systems are crucial

as they relate to using and managing these resources. Water is

essential for all forms of life and crucial for human development.

Water systems, including oceans, wetlands, coastal zones, surface

waters and acquifers provide a vast majority of environmental

goods and services, including drinking water, transport and food.

Today, women should continue to be positive agents of change,

in both developmental and environmental causes, because the female

nature has a more holistic, symbiotic relationship with the surroundings.

Although often limited by preconceived assumptions regarding

their gender's role in society, women, by nature, would make

better and more effective nurturers of the sea-world.

It is suggested therefore, during the process of environmental

impact assessments for developmental projects, the identification

of gender dichotomies, as well as comprehensive gender analyses

should be included as an essential ingredient of the formula.

This approach empowers women and may result in more efficient,

sustainable development of local areas and the overall welfare

of communities.

Conclusion

Throughout the circum-Mediterranean

area, great matriarchal civilizations flourished (e.g. Anatolian,

Minoan & Cycladic, Etruscan), embedded with a rich variety

of feminine symbolic expressions. The implied symbolisms in mythology

strongly suggest that women constituted a significant and active

force in sustaining the development of ancient communities, safeguarding

their resources, nurturing youth and ensuring continuity of social

and cultural values. Because of the more holistic and symbiotic

relationship with their surroundings, women have always been

positive agents of change in protecting aquatic resources - a

role that must be properly acknowledged, appreciated and encouraged,

now and in the future.

References

Burkert, W. (1993):

The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influences on Greek

Culture in the Early Archaic Age. Harvard University Press

Dalley, Stephanie

(1987): Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Gimbutas, Marija (1974):

The Goddesses and

Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images (6500-3500 B.C.). Thames and Hudson, London.

Gimbutas, Marija (1989):

The Language of the

Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization. Thames and Hudson, New York.

Gimbutas, Marija (1991):

The Civilization

of the Goddess. Harper

Collins, New York.

Jacobsen, Th. (January-March

1968): The Battle

between Marduk and Tiamat.

Journal of the American Oriental Society vol. 88 (1), pp. 104-108

Kramer, S.N. (1944):

Sumerian mythology. Memoirs of The American Philosophical

Society Series vol. 21. Lancaster Press, Lancaster, PA.

Return to

Return to

Links to other

Pages

Links to other

Pages

now available from Amazon, Barnes

and Noble and other major bookstores. It can be also ordered

by contacting directly Aston

Forbes Press.

now available from Amazon, Barnes

and Noble and other major bookstores. It can be also ordered

by contacting directly Aston

Forbes Press.

Now available

from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other major bookstores. A signed

by the author copy can be also ordered by contacting directly

by email Aston

Forbes Press.

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

|