|

THE EARTHQUAKE

AND TSUNAMI OF 29 NOVEMBER 1975 IN THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

George

Pararas-Carayannis

(Excerpts

from a post-Tsunami Survey conducted on 30 November - 3 December,

1975, and from subsequent reports)

Introduction Introduction

On Wednesday, 29 November 1975,

the largest local earthquake to strike the Hawaiian Islands since

1868 - subsequently named the Kalapana Earthquake of 1975 - generated

the most destructive local tsunami of the 20th Century. The earthquake

was particularly damaging in Hilo. The tsunami was particularly

destructive on the southern, eastern and western coasts of the

Island of Hawaii. There was extensive damage at Keahou Landing,

Punalu'u, Honuapo, Kaalualu Bay and at Keahou. The tsunami's

far field effects were negligible. There was minor damage to

boats and harbor facilities on Catalina Island in California. On Wednesday, 29 November 1975,

the largest local earthquake to strike the Hawaiian Islands since

1868 - subsequently named the Kalapana Earthquake of 1975 - generated

the most destructive local tsunami of the 20th Century. The earthquake

was particularly damaging in Hilo. The tsunami was particularly

destructive on the southern, eastern and western coasts of the

Island of Hawaii. There was extensive damage at Keahou Landing,

Punalu'u, Honuapo, Kaalualu Bay and at Keahou. The tsunami's

far field effects were negligible. There was minor damage to

boats and harbor facilities on Catalina Island in California.

The Kalapana

Earthquakes of 1975

Two earthquakes occurred

on 29 November 1975. The first was a foreshock at 13:35 GMT (3:35

a. m local time) with 5.7 magnitude and epicenter near Lae'apuki

on Kilauea volcano's southern flank. The second and larger earthquake

occurred a little over an hour later, at 14:48 GMT (4:48 a.m.

local time). Its Richter magnitude was 7.2 and its epicenter

was at 19.3 N, 155.0 W - near Kamoamoa - just a few miles east

(immediately off the southeast coast) but closer to the shore

than the earlier foreshock. Its focal depth was only 8 km below

the surface, near the magmatic chambers of Kilauea volcano's

Puna Rift Zone.

Damages

and Death Toll

Although the major

Kalapana earthquake had a rather large surface-wave magnitude

of 7.2, there was relatively minor damage to about a dozen homes

within 10 miles of the epicenter. However, at Hilo, about 45

miles from the epicenter, the damage was heavy to the Hilo Hospital

and several other substantial buildings.

The death toll was

remarkably low but that was because the earthquake (and the tsunami)

occurred in a region of the Island of Hawaii with low population

density at the time. Only two people lost their lives and twenty-eight

(28) were injured. The deaths, injuries, and about a third of

the property damage, were caused by the tsunami.

Total property damage

losses in the Hawaiian Islands from both the earthquake and tsunami

were estimated at about $4.1 million (1975 dollars). Of the property

losses, about $2.1 million was to private property and about

$2 million to public property.

Crustal

Displacements

The major earthquake

of 29 November 1975 occurred east of the area that had been affected

by the earthquake of 3 April 1868. The crustal movements involved

uplift, subsidence and slope failure along the Hilina Slump of

the Kilauea volcano, on the southern coast of the Island of Hawaii.

A large crustal block slid horizontally towards the ocean and

partly subsided, while the offshore area uplifted.

Maximum horizontal

displacement of approximately 7.9 meters (26 feet) and vertical

subsidence of approximately 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) occurred near

Keahou Landing. The displacements decreased to the east and west.

In fact, subsidence decreased rapidly to the west. At Punalu'u,

the shoreline actually uplifted by about 10 centimeters (4 inches)

(Pararas-Carayannis 1975).

Subsequent surveys

determined subsidence of about 3 meters (9.8 feet) at Halape

Park to the east. The large coconut grove area adjacent to the

Beach Park subsided by as much as 3.0 and 3.5 meters (10-11.5

feet). Further to the east, the subsidence decreased to 1.1 meters

(3.6 feet) at Kamoamoa, 0.8 meters (2.6 feet) at Kaimu, 0.4 meters

(1.3 feet) at Pohoiki, and 0.25 meters (0.8 feet) at Kapoho.

The coastline was

not the only altered area. According to the Volcano Observatory

of the U.S. Geological Survey, even the summit of Kilauea subsided

by about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) and moved towards the ocean by

about the same amount. A small, short-lived eruption took place

inside Kilauea's caldera, apparently triggered by the earthquake.

A better understanding

of the pattern of displacements in the offshore region was deduced

from inspection of the local tide gauge records of the tsunami.

The records show an upward initial tsunami wave motion (see tide

gauge records below). This indicates that the offshore portion

of the displaced crustal block actually uplifted, as the onshore

section subsided and moved outward. Also, this pattern of crustal

movement indicates that the flank failure of Kilauea was not

entirely due to gravitational effects of instability, but may

have been partially caused by compressional lateral magma migration

from shallow magmatic chambers of the volcano, or by lateral

magmastatic forces along an arcuate failure surface, or along

a secondary zone of crustal weakness on the upper slope of the

Hilina Slump. In fact, recent paleomagnetic studies (Riley et

al., 1999) show that differential rates of movement and rotation

occur between sections of the Hilina Slump. This would support

that Kilauea's flank failures can be triggered by several mechanisms.

Aerial

view of permanent subsidence ranging from 3.0 to 3.5 meters at

the Halape Beach Park coconut grove on Hawaii Island. (Photo:

National Park Service)

Aerial

view of permanent subsidence ranging from 3.0 to 3.5 meters at

the Halape Beach Park coconut grove on Hawaii Island. (Photo:

National Park Service)

Historical

Earthquakes on the southern Island of Hawaii have been caused

by a variety of flank failures triggered by volcanic, tectonic,

isostatic, gravitational and earth tide mechanisms (modified

web graphic).

Historical

Earthquakes on the southern Island of Hawaii have been caused

by a variety of flank failures triggered by volcanic, tectonic,

isostatic, gravitational and earth tide mechanisms (modified

web graphic).

THE

TSUNAMI OF 29 NOVEMBER 1975

THE

TSUNAMI OF 29 NOVEMBER 1975

The tsunami of 29

November 1975 was the first major tsunami of local origin to

strike the Hawaiian Islands since 1868. The waves were particularly

destructive along the southern coast of the Island Hawaii, but

less destructive along the eastern and western parts of the island.

The tsunami killed two and injured 19 more people at Halape beach,

on the southern coast of the Island. Tide gauges in the Hawaiian

Islands and on the West Coast, Alaska, Japan, and Pacific islands

recorded the tsunami. (Cox and Morgan, 1977, p. 57-72; Pararas-Carayannis

and Calebaugh, 1977, Soloviev et al., 1986, Loomis, 1975).

Tsunami Warning Tsunami Warning

The travel time of

the first of the tsunami waves along the southern coast of the

Island of Hawaii ranged from less than a minute to as long as

15 to 25 minutes. A local Tsunami Warning was issued by Hawaii

's Civil Defense Agency. However, because of the short interval

between the earthquake and the arrival of the tsunami, the warning

was issued after the first wave had already struck the southern

part of the Island of Hawaii. The first of the waves struck Punalu'u

only 84 seconds after the earthquake.

Near Field

Tsunami Effects

A comprehensive post-tsunami

survey of the immediate tsunami generating area and of the eastern

and western coast of Hawaii was undertaken by the author and

Lt. Dennis Sigrist which documented the tsunami's near field

effects (Pararas-Carayannis, 1975). Reports appeared in the ITIC

Tsunami Newsletter (Vol. VIII, No. 4, December, 1975) and in

the ITIC Director's ITSU bi-annual report. The following is a

summary report of the effects of the tsunami in the Hawaiian

Islands.

Halape The Halape

area was part of the crustal block of the tsunami generating

area that subsided. As the photos show, the ground where there

was a large coconut grove area adjacent to the Beach Park at

Halape subsided by as much as 3.0 and 3.5 meters (10-11.5 feet).

The grove itself was left submerged in 1.2 m of water.

There were thirty-two

campers at Halape when the earthquakes occurred and later when

the second earthquake generated a major tsunami. There are several

eyewitness accounts in the literature concerning the events at

the park that night, so they will not repeated here. According

to the campers, the first tsunami wave observed at Halape was

only 1.5 meters (almost 5 feet). However, the second wave was

7.9 meters (about 26 feet). Two people were killed and nineteen

more were injured. Four horses were drowned. The highest was

the second wave, which reached 14.6 m above the post submergence

level of the sea. Subsequent waves were much smaller

Another photograph

of the coconut grove at Halape Beach Park (Photo credit: P.W.

Lipman taken on December 3, 1975)

Keahou Landing - A maximum tsunami runup of 14.3 meters (almost

47 feet) was measured at the Keauhou Landing, where the waves

completely destroyed the pier and overturned large fuel tanks. Keahou Landing - A maximum tsunami runup of 14.3 meters (almost

47 feet) was measured at the Keauhou Landing, where the waves

completely destroyed the pier and overturned large fuel tanks.

Punalu'u - The first wave was relatively

small and arrived only 84 seconds after the earthquake. The largest

wave arrived about 10 minutes later and was particularly destructive.

Maximum tsunami run-up was 7.6 meters (about 25 feet) and penetrated

about 137 m (450 ft) inland. The second wave destroyed seven

houses, a large restaurant, a gift shop, and two cars. Four concrete,

steel-reinforced beams in front of the beach pavilion were either

toppled or bent severely due to the waves Coconut trees were

severed by the destructive force of the waves. Total damage amounted

to about $1 million (1975 dollars).

Tsunami destruction

at Punalu'u (Photo: G. Pararas-Carayannis taken 29 Nov 1975)

Honuapo - The tsunami damaged a fishing

pier, the beach park facilities and a warehouse.

Kaalualu Bay - The waves damaged vehicles campsites

and destroyed canoes. At Napoopoo a shed was moved off its foundations.

Keahou There was damage to dock facilities

and boats. One boat was carried by the waves and deposited in

the parking lot. Another boat sank, and other boats and the dock

facilities were damaged.

Hilo - A timely tsunami watch by Hawaii's

Civil Defense Agency resulted in evacuation of low-lying areas.

The water begun to recede at 5:10 A.M. - draining the harbor.

The Coast Guard Cutter U.S.S. Cape Small settled into the harbor

bottom and listed. The waves sunk four boats and damaged three

others. A car was swept off the pier into the bay. The maximum

observed tsunami wave height at the mouth of Wailoa River was

about 12 feet.

Lahaina - Maui - There were reports of sailboats

hitting bottom at the harbor

Hana Maui - No report of damage. A fisherman

reported unusual recession of the water at 5:30 A.M.

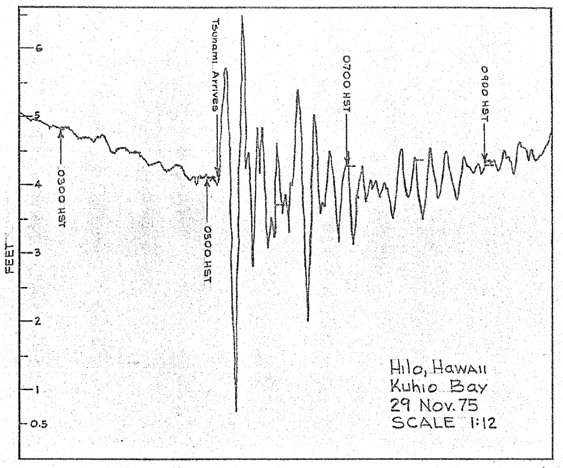

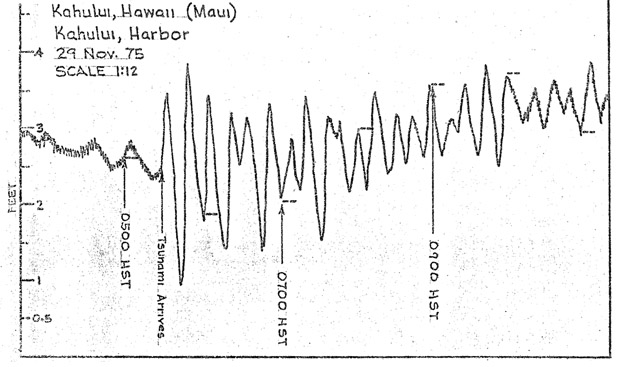

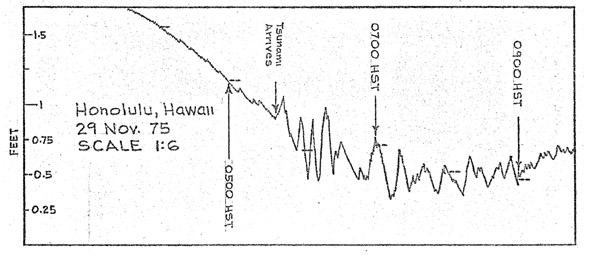

The Tsunami

of 29 November 1975 as Recorded by Tide Stations in the Hawaiian

Islands

A relatively small

tsunami was recorded by tide gauges in the harbors of Hilo, Kahului,

Honolulu and Nawiliwili (Pararas-Carayannis, 1975). Copies of

the tide gauge recordings were provided in the ITIC Tsunami Newsletter

(Vol. VIII, No. 4, December, 1975).

The following maximum

heights were recorded: Hilo, Hawaii 5.7 feet; Kahului, Maui 3.0

feet; Honolulu, Oahu: 0.1 feet; Nawiliwili, Kauai 0.9 feet. The

actual tsunami runup on open water coast locations was considerably

higher than what was recorded by tide gauges which were located

in more sheltered areas. For example maximum observed tsunami

wave height at the mouth of Wailoa River was 12 feet while the

maximum recorded by the Hilo gauge was 5.7 feet.

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Hilo Tide Gauge

on the Island of Hawaii

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Hilo Tide Gauge

on the Island of Hawaii

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Kahului Tide

Gauge on the Island of Maui.

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Kahului Tide

Gauge on the Island of Maui.

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Honolulu Tide

Gauge on the Island of Oahu

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Honolulu Tide

Gauge on the Island of Oahu

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Nawiliwili Tide

Gauge in the Island of Kauai.

The

Tsunami of 29 November 1975, as Recorded by the Nawiliwili Tide

Gauge in the Island of Kauai.

Far Field

Tsunami Effects

In addition to the

tide stations in the Hawaiian Islands, many other tide stations

on the U.S. West Coast, Alaska and Japan recorded a minor tsunami.

Also, minor tsunami waves were recorded in American Samoa and

in Western Samoa and several other Pacific islands. (Cox and

Morgan, 1977, p. 57-72; Pararas-Carayannis and Calebaugh, 1977;

Pararas-Carayannis and Dong, 1980; Soloviev et al., 1986, Loomis,

1975).

Alaska - The Yakutat tide gauge recorded

a wave of 2 inches in amplitude. The Sitka gauge recorded a wave

of 4 inches in amplitude.

American Samoa - The Pago Pago tide gauge recorded

a wave with amplitude of 0.11 m.

Western Samoa - The Apia station recorded a 0.17

m oscillation.

California - In California, there was minor

damage to harbor facilities on Catalina Island. Tsunami waves

of up to nine feet at the Isthmus Harbor destroyed a small floating

dock and broke loose another floating dock. According to newspaper

accounts, the water receded and several boats were stranded on

the bottom of the harbor but refloated by subsequent waves (San

Pedro Pilot, December 1, 1975). A small surge occurred at Marina

del Rey near Santa Monica (Santa Monica Evening Outlook, December

1, 1975; Spaeth, 1977; Soloviev et al., 1992).

Tsunami Generating

Area Tsunami Generating

Area

As with the 1868 event,

Hilo was greatly affected by the shock waves of the 1975 earthquake

but not as much by the tsunamis generated by these events. This

is suggestive of the directionality of slumping and of the limited

dimensions of distinct slope failure events along the southern

flanks of the Kilauea and Mauna Loa volcanoes.

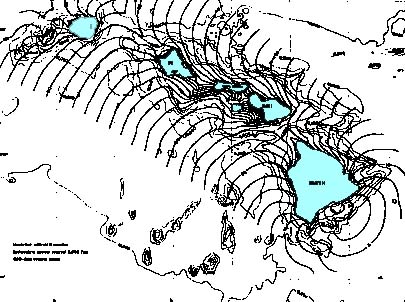

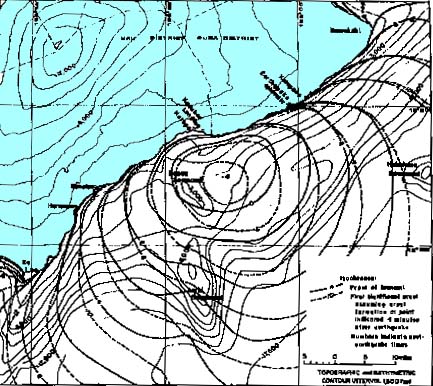

Hawaii's southern

coast showing coastal faults parallel to the east rift zone of

the Kilauea volcano, and the Generation Area of the 1975 Tsunami

in relation to the Hilina Slump where flank failures have occurred

in the past (Base map modified after Morgan et al. 2001).

Slope failures and

subsidence along Kilauea southern flank have been frequent in

the past and have generated local destructive tsunamis. However,

flank failures associated with the more recent earthquakes, appear

to have occurred in phases, over a period of time, and not necessarily

as single, large-scale events involving great volumes of crustal

material. However, large prehistoric flank failures appear to

have occurred, particularly along the western flank of the Mauna

Loa volcano. Such failures must have generated large local tsunamis

in the past.

As described previously,

a large crustal block of the flank of the Kilauea volcano slid

horizontally towards the ocean and subsided, while the offshore

region uplifted (Pararas-Carayannis 1975). Although there was

considerable subsidence along the coast, the entire offshore

region of tsunami generation is estimated to have risen by an

average of about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet). Since the initial wave

motion of the tsunami at all recording tide gauge stations in

the Hawaiian Islands was upwards, it strongly supports that the

offshore area uplifted.

The offshore crustal

displacements correspond to the tsunami generating area, which

is estimated to be about 70 km long and 30 km wide with the long

axis of the displaced crustal block being parallel to the coast.

Although these represent estimates, the volume of displaced water,

as well as the total energy that went into tsunami generation

can be calculated. The total volume of displaced material that

contributed to tsunami generation was roughly estimated to be

2.52 cubic km (Pararas-Carayannis 1976 a, b).

Generating Mechanism

of the 1975 Tsunami in Hawaii Generating Mechanism

of the 1975 Tsunami in Hawaii

A sudden flank collapse

process generated the 1975 tsunami, which was closely associated

with Kilauea's ongoing volcanic activity and the instability

of the volcano's southern flank. Such instability along fractures

controlled by regional faults along the Puna Rift Zone results

in both aseismic and seismic slippage. The offshore geomorphological

features on the Hilina Slump - and the tide gauge recordings

of the tsunami - indicate that the 1975 flank failure and earthquake

were triggered by compressional forces of moving lava within

Kilauea's magmatic chambers below and within ascending lava dikes

- having a hydraulic piston effect on a weakened flank crustal

block. Gravitational settling followed the crustal movement.

This appears to be the mechanism by which most flank failure

events occur on Kilauea and the Mauna Loa volcanoes.

In conclusion, therefore,

the tsunami was generated by the combination of the net sudden

subsidence and uplift of the ocean floor, as well as from the

lateral crustal compression of a crustal block in a seaward direction.

The compression and the lateral crustal movement on the Hilina

Slump probably formed a horst in the offshore region. This horst

would demarcate the outer edge of the tsunami generation area

and the origin of the faster first tsunami wave. This would explain

the initial upward wave motion recorded by the tide gauges around

the islands. The faster traveling wave originated along the deeper

offshore perimeter of the tsunami generating area. The tsunami

travel times also support this conclusion.

Such flank failure

processes are characteristic of the mechanisms of earthquakes

that occur with frequency along the southern coast of the Island

of Hawaii. Tsunamigenic earthquakes occur when aseismic slippage

stops due to locking along the coastal faults and critical stresses

build up along potential decollment surfaces. The magmastatic

pressures or moving lava in the volcano's chambers or along flank

dikes, or even gravitational forces or tidal forces (including

earth tides) can trigger the release of the stored stress. Larger

earthquakes occur with the more significant flank failures. Most

of the time, Kilauea's southern flank along the Hilina Slump

region, slips aseismically without tsunami generation. However,

larger failures occur although separated by decades in time.

Tsunami Travel Times

and Runup Tsunami Travel Times

and Runup

Subsequently to this

author's initial 1975 field survey, there were numerous other

reports pertaining to the time of arrival of the first tsunami

wave at different locations around the Hawaiian Islands, the

heights of subsequent waves, and the maximum observed runup.

Cox and Morgan (1977) summarized these reports and prepared the

tsunami refraction diagrams shown here. Also, for the purpose

of hazard zonation, Cox (1979) estimated the runup heights of

the 1975 tsunami for places where there had been no actual physical

measurements or observations. For the immediate tsunami generating

area where there had been substantial subsidence, the given runup

height estimates were based on the pre-subsidence mean sea level

datum. Although Cox somewhat underestimated the dimensions of

the tsunami generating area, the tsunami travel times are fairly

accurate for the initial wave which originated in deeper water

off the Kalapana coast. As pointed earlier, the actual tsunami

runup on open water coast locations around the Hawaiian Islands

were considerably higher than what was recorded by tide gauges

in sheltered harbors.

Past and

Future Tsunamis Vulnerability of the Hawaiian Islands to

Local Tsunamis

Failure of the southern

flank of Kilauea (and Mauna Loa) is an ongoing process that has

been responsible for numerous earthquakes and local tsunamis

throughout Hawaii's geological history.

The numerous faults

(palis) along the Puna Rift Zone with their tilting walls indicate

a seaward progression of edifice failure. Also, the numerous

"horsts" and "grabens" in the offshore region

of the Hilina Slump as well as toes of debris avalanches

on the ocean floor - indicate that past flank failures and associated

earthquakes resulted from gravitational and volcanically-induced

compressional forces.

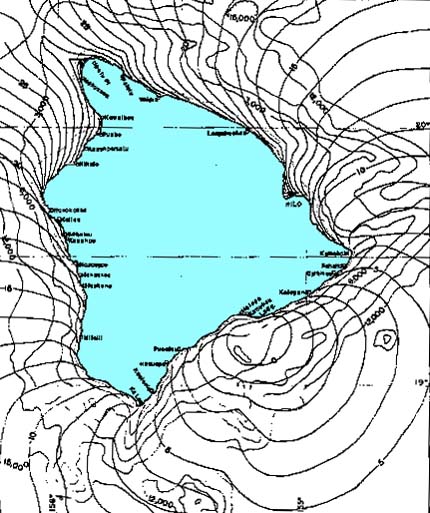

Composite Satellite

Photo of the Island of Hawaii (8 photos)

The offshore geomorphological

features are characteristic of large crustal block movements

from past earthquakes and parallel those of the 1975 Kalapana

event. The failures appear to have occurred as discreet events

along the submarine portion of the Hilina Slump over a long period

of time. Such discreet failures have generated destructive tsunamis

in the past. The destructive local tsunamis of 1823(?) and 1868

were generated by such flank failures of Kilauea and Mauna Loa

volcanoes. In 1989, the southern region of Hawaii experienced

smaller, damaging earthquakes, but no tsunami was generated.

In view of the instability of

the southern flanks of Kilauea (and of Mauna Loa), the area is

vulnerable to local tsunamis. In older times this was not as

critical since the population density was low. However, since

1975 the population density on the southern coast of the Island

of Hawaii has increased dramatically. Thus, a repeat of an earthquake

and tsunami as in 1975, can be expected to result in many more

casualties and extensive property losses. In view of the instability of

the southern flanks of Kilauea (and of Mauna Loa), the area is

vulnerable to local tsunamis. In older times this was not as

critical since the population density was low. However, since

1975 the population density on the southern coast of the Island

of Hawaii has increased dramatically. Thus, a repeat of an earthquake

and tsunami as in 1975, can be expected to result in many more

casualties and extensive property losses.

Tsunami preparedness

for the Hawaiian Islands and particularly the Island of

Hawaii must take into consideration the increased level

of risk associated with the recent development of the coastal

areas. Appropriate measures must be taken to factor the added

risk to any community development and the construction of supporting

infrastructure.

REFERENCES

AND ADDITIONAL READING

Cox and

Morgan, 1977

Loomis, 1975

McMurtry

G. M., Herrero-Bervera E., Cremera M. D., Smith J. R., Resig

J., Sherman C. and Torresan M. E., 1999. Stratigraphic constraints on the timing

and emplacement of the Alika 2 giant Hawaiian submarine landslide.

Journal

of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Vol. 94 (1-4) (1999)

pp. 35-58.

Moore, J.G.,

and Chadwick, W.W. Jr., 1995. Offshore geology of Mauna Loa and adjacent areas,

Hawaii.

In Geophysical Monograph 92, Mauna Loa Revealed: structure, composition,

history, and hazards, ed. by J.M. Rhodes and J.P. Lockwood, American

Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., p. 21-44.

Moore, J.G.,

and Clague, D.A., 1992. Volcano growth and evolution of the island of

Hawaii.

Geologic Society of America Bulletin, 104, 1471-1484.

Moore, J.G.,

Clague, D.A., Holcomb, R.T., Lipman, P.W., Normark, W.R., and

Torresan, M.E., 1989. Prodigious submarine landslides on the Hawaiian

Ridge.

Journal of Geophysical Research, Series B 12, Volume 94, p. 17,465-17,484.

94, 17,465-17, 484.

Moore, J.G.,

Normark, W.R. & Holcomb, R.T., 1994. Giant Hawaiian Landslides. Annual Reviews of

Earth and Planetary Science, 22, 119-144.

Morgan,

J.K., Moore, G.F., and Clague, D.A., 2001. Papa`u Seamount: the submarine expression

of the active Hilina Slump, south flank of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. Journal of Geophysical

Research, submitted.

Pararas-Carayannis,

G. 1968. Catalog

of Tsunamis in the Hawaiian Islands. Data Report Hawaii Inst.Geophys.

Jan. 1968

Pararas-Carayannis,

G., 1969. Catalog

of Tsunami in the Hawaiian Islands. World Data Center A- Tsunami U.S.

Dept. of Commerce Environmental Science Service Administration

Coast and Geodetic Survey, May 1969.

Pararas-Carayannis

G., 1975.

Tsunami Newsletter,

Vol. VIII, No. 4, December, 1975.

Pararas-Carayannis,

G., 1976a. The

Earthquake and Tsunami of 29 November 1975 in the Hawaiian Islands. ITIC Report, 1976.

Pararas-Carayannis,

G., 1976b. In International Tsunami Information Center - A Progress Report For

1974-1976.

Fifth Session of the International Coordination Group for the

Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific, Lima, Peru, 23-27 Feb.

1976

Pararas-Carayannis,

G. and Calebaugh P.J., 1977. Catalog of Tsunamis in Hawaii, Revised and Updated, World Data Center

A for Solid Earth Geophysics, NOAA, 78 p., March 1977.

Pararas-Carayannis,

G. and Dong B. 1980. A

Study of Historical Tsunami in American Samoa for U.S. Corps.

of Engineers, Waterways Experiment Station Type 16 Flood Studies. Honolulu: Research

Corporation University of Hawaii, October 29, 1979, Waterways

Experiment Station Report 1980.

Pararas-Carayannis,

G, 1988. Risk

Assessment of the Tsunami Hazard. In Natural and Man-Made Hazards, 1988,

D. Reidal, Netherlands, pp.171-181.

Pararas-Carayannis,

George, 2002. Evaluation

of the Threat of Mega Tsunami Generation from Postulated Massive

Slope Failures of Island Stratovolcanoes on La Palma, Canary

Islands, and on the Island of Hawaii, Science of Tsunami Hazards. Vol 20

(5). pages 251-277, 2002 ALSO AT URL http://www.drgeorgepc.com/TsunamiMegaEvaluation.html

Pararas-Carayannis,

G., 2005. INSTABILITY

OF KILAUEA VOLCANO'S SOUTHERN FLANK - EVALUATION OF MASS EDIFICE

FAILURES, FLANK COLLAPSES AND POTENTIAL TSUNAMI GENERATION

Pararas-carayannis, G., 2004. VOLCANIC

TSUNAMI GENERATING SOURCE MECHANISMS IN THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN

REGION

Pararas-Carayannis, G., 2004. Factors

Contributing to Explosivity, Structural Flank Instabilities,

Mass Edifice Failures and Debris Avanlanches of Volcanoes - Potential

for Tsunami Generation

Reynolds,

J. R., Clague, D.A., Hatcher, G. and Maher, N., 1998. Evolutionary Sequence

of Submarine Volcanic Rift zones in Hawaii. EOS, Transactions American Geophysical

Union, 79, F825.

San Pedro Pilot, December 1, 1975 / Santa Monica Evening Outlook,

December 1, 1975

Shigihara,

V., and Imamura, F., 2002. Numerical Simulation Landslide Tsunami 2nd Tsunami Symposium,

Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, May 28-30, 2002

Smith, J.

R. Malahoff A., and Shor A. N., 1999. Submarine geology of the Hilina slump

and morpho-structural evolution of Kilauea volcano, Hawaii. Journal of

Volcanology and Geothermal Research, V. 94, No 1-4, 1, pp. 59-88

December U.S. Geological Survey, Hawaii Volcano Observatory,

Survey

Soloviev

et al., 1992.

Soloviev et al., 1986

Spaeth, 1977

Tilling,

R.I., Koyanagi, R.Y., Lipman, P.W., Lockwood, J.P., Moore, J.G.,

and Swanson, D.A., 1976. Earthquake and related catastrophic events, Island

of Hawaii,

November 29, 1975: a preliminary report: U.S. Geological Survey

Circular 740, 33 p.

SEE ALSO

INSTABILITY OF KILAUEA VOLCANO'S SOUTHERN FLANK

- EVALUATION OF MASS EDIFICE FAILURES, FLANK COLLAPSES AND POTENTIAL

TSUNAMI GENERATION

EVALUATION OF THE THREAT OF MEGA TSUNAMI GENERATION

FROM POSTULATED MASSIVE SLOPE FAILURES OF ISLAND STRATOVOLCANOES

ON LA PALMA, CANARY ISLANDS, AND ON THE ISLAND OF HAWAII

VOLCANIC TSUNAMI GENERATING SOURCE MECHANISMS

IN THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN REGION

Factors Contributing to Explosivity, Structural

Flank Instabilities, Mass Edifice Failures and Debris Avanlanches

of Volcanoes - Potential for Tsunami Generation

Return to

Return to

Links to other

Pages

Links to other

Pages

Now available

from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other major bookstores. A signed

by the author copy can be also ordered by contacting directly

by email Aston

Forbes Press.

Now available

from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other major bookstores. A signed

by the author copy can be also ordered by contacting directly

by email Aston

Forbes Press.

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

Other

Miscellaneous Non-technical Writings

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

(©) Copyright

1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information

on this site is for viewing and personal information only - protected

by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material

from this site without written permission is prohibited.

|